HEAD to HEAD

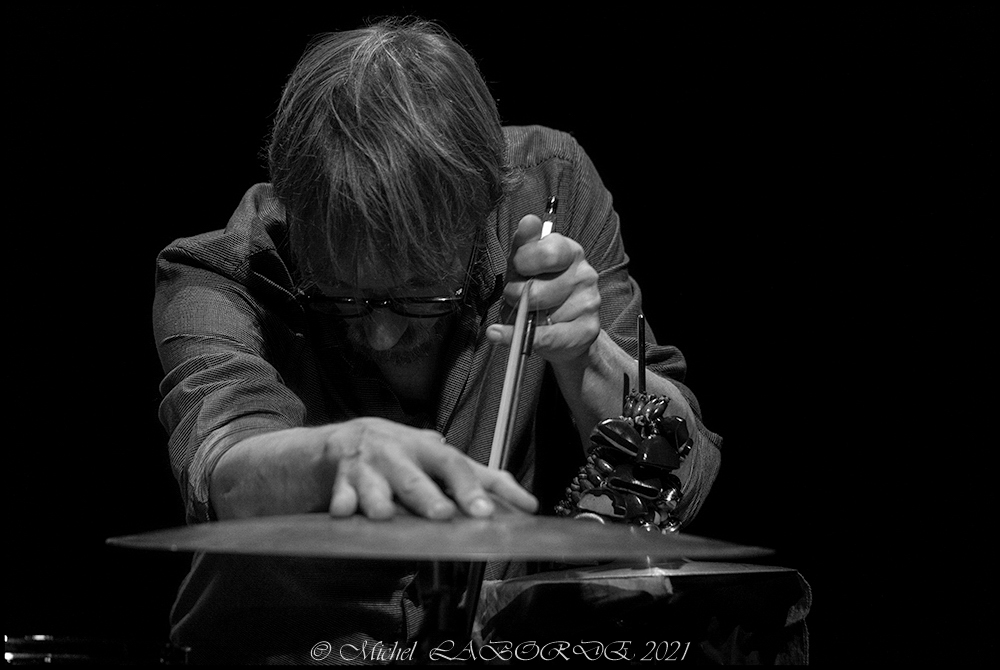

Peter Orins

‘Head to Head’ is a series of interviews by Sound in Motion’s Joachim Ceulemans, talking in depth with artists appearing in the Oorstof concert series, the Visitations residencies, the Summer Bummer Festival or who have a release on the Dropa Disc label. These interviews will be used to promote the upcoming events and releases and who knows, maybe they will end up bundled and printed one day.

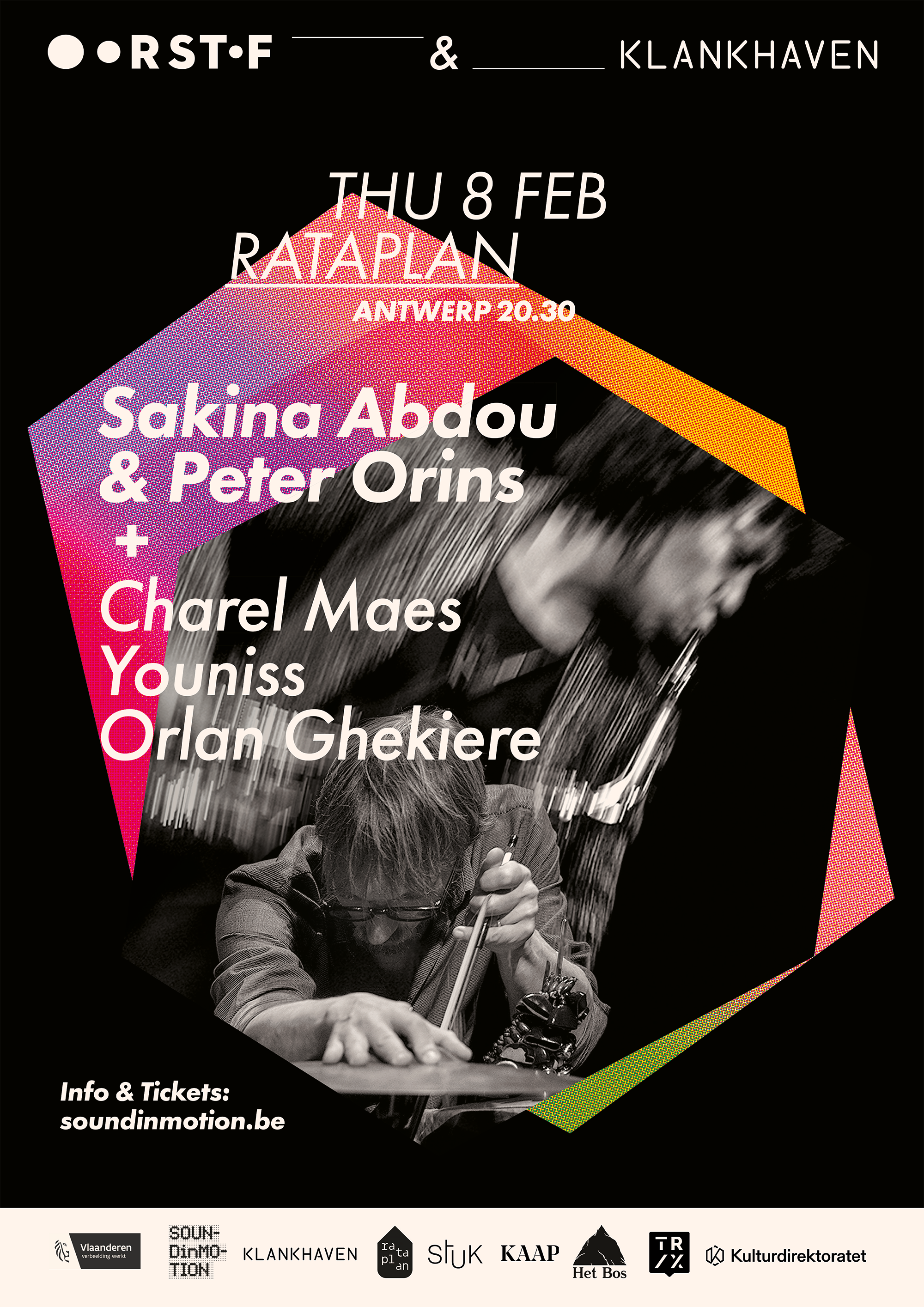

Drummer, composer, improviser, bandleader, curator, … many labels apply for Lille-based artist Peter Orins. He is not only very prolific and active in many different bands and projects (Kaze, Trapeze, TOC, …) but he also runs the Circum Disc label and is the artistic leader of the Muzzix collective. In February, he will play a rare duo show with saxophonist and flautist Sakina Abdou at Rataplan.

When I was listening to and reading about some of your recordings, I noticed a broad range of influences, from composers like James Tenney to The Necks and Sonic Youth. Stylistically, your music is mostly connected to free improvisation, free jazz and contemporary composition, so let me start by asking how you got into that music.

When I was younger I wanted to play jazz because I was really attracted to it. At about age 15 or 16 I got to know the music of saxophonist Tim Berne and that really changed the way I thought about jazz. Together with a friend I started to do that kind of music in the conservatory, around the age of 20. The jazz department of the conservatory in Lille had a few teachers with a background in free jazz, like trumpet player Jean-François Canape (1945-2012), who influenced me a lot. It was nice to be able to approach jazz from another angle, instead of the classical way. Around that time in 1998, the CRIME collective was founded. It stood for Centre Régional d’Improvisation de Musique Expérimentale and they tried to bring together all the musicians who wanted to improvise and do experimental music. It included different musicians from various genres and fields of music, from rock, classical music and jazz. They started to organize improvisation workshops. At that time I was still more into jazz, but many people around me were working with that collective and they invited me to join a big orchestra called La Pieuvre, which was an experiment for more than 10 years to try and improvise in a big orchestra with around 25 musicians with a conduction style influenced by Butch Morris. The collective organized a lot of concerts and brought many international musicians to Lille, which was kind of a new thing in that period. Although there was a tradition of free jazz in the city in the late 60s and 70s, which shifted to straight jazz in the 80s until the collective came and started organizing concerts in the venue we still use now: La Malterie.

How big was the CRIME-collective?

It wasn’t really formal, but it was something between 20 and 30 musicians, a very diverse group of musicians considering age, background and all that. I was leading another collective called Circum, which was more jazz oriented with musicians coming from the conservatory who had professional ambitions. We started working together and in 2010 merged into the Muzzix collective. I guess that’s how I discovered all that music, by organizing concerts and meeting musicians with different backgrounds and interests.

Can you tell me something more about the free jazz scene in Lille in the late 60s and the 70s? Because I don’t think it’s that well-known.

Well, I wasn’t born yet so I didn’t experience it myself. I know the music was more popular than now. The location of Lille, on the boarder of France and Belgium, was of course very convenient, also for meeting musicians from Germany, The Netherlands or England. There were local musicians like guitarist Jean-François Pauvros and international artists like Fred Van Hove who performed here. The critic and photographer Gérard Rouy, was also an important part of that scene and actually a lot of what I know of that period comes from his stories.

I read that in the nineties, Fred Van Hove was leading a workshop course at the conservatory in Lille.

It was not at the conservatory but at the university, in the musicology department. I was there for a brief time of my life. I spent two years at the university with him and it was a big opportunity to be exposed to that music. I wasn’t easy for him because his students there mostly came from classical music and they didn’t really understand what he was doing. But it was quite something to have him and to be able to work with him. He organized workshops around improvisation and we also invited him to join La Pieuvre as a guest. In turn, he asked us to perform at his Free Music festival in Antwerp.

Did he use composed material for the workshops as a base for the improvisation?

No, it was really free improvisation. But it’s already such a long time ago, maybe thirty years. The memory I have of it is me really struggling with it and also seeing other musicians struggling or simply not understanding it. It wasn’t easy, but I consider myself really lucky to have had that experience.

You’re the artistic leader of the Muzzix collective. What does the organization do?

The main idea is to create opportunities for the musicians to be able to do new projects and new creations. There are about 30 musicians involved, with about 10 of them leading projects from solos to big orchestras. We try not to be stuck in one aesthetic so it goes from some kind of jazz to free jazz, experimental and contemporary music and of course a lot of improvisation too. That causes problems because some people think we do jazz and others think we are too experimental. But that’s the way it is I guess. The idea of it all is to really experiment with new ways of making music and new ways of listening to music. All the members are linked to the Lille area, so that’s a big part of the collective’s identity. In the beginning, we were hoping that by organizing concerts, other promotors would be inspired to book this kind of music, but that didn’t really happen. We also work with different kinds of audiences, school children or even social workers to show them the richness and diversity of music. This is all centered around La Malterie. We also try to promote internationally by organizing tours.

In La Malterie, there are also workshops and jam sessions happening regularly. Are they also being organized by Muzzix?

Yes, together with the jazz department of the conservatory. It gives them the opportunity to do jam sessions under better conditions. We have a piano and some backline so that helps a lot. The idea also was to bring students to La Malterie and to make them know what happens here. These are really jazz jam sessions and for some months we also started organizing free improvisation jams once a month which is also a way for us to bring new musicians in. The collective is pretty big but we are also getting older, it’s been here for 25 years. We not only want to meet younger musicians but also expose ourselves to new things and attract new audiences.

Are you succeeding in that? I know it’s a hot topic related to these types of music. There are a lot of interesting young bands and musicians, but it’s hard to reach new audiences.

For sure. I think, in general, we are able to bring younger people in than in other venues in France for this kind of music, because there is a lot going on at La Malterie, different organizations and lots of activities. There are some rehearsel spaces as well so there are many musicians working there all the time. We succeed partly in bringing musicians from different fields, like rock music, via workshops. That’s very interesting for us. But it’s not easy to reach people for instance in their early 20s. There are young people playing this music, but what also happens is that they move to Paris or Brussels, where there’s a lot more happening.

Saxophonist and flutist Sakina Abdou is also from Lille and part of the Muzzix collective. You will be playing with her in duo in Antwerp soon. The duo is something you rarely do, is that correct?

Yes. We played a duo in Portugal in November and that was the second time ever. The first time was a few years ago and something very different from what we did now. We were in a kind of residency in Porto, in a great place called Sonoscopia. I mostly played electronics, which is something I play a lot in my solo shows, but not so much with other people. I guess I will focus more on my drums for the concert in Antwerp.

The two of you have a trio together with pianist Barbara Dang and you released an intriguing record called ‘Lescence/Gmatique’. The music is minimalistic and in “ultra-reduced sound volume”, according to the liner notes. Can we expect the same from the duo with Sakina?

The two of you have a trio together with pianist Barbara Dang and you released an intriguing record called ‘Lescence/Gmatique’. The music is minimalistic and in “ultra-reduced sound volume”, according to the liner notes. Can we expect the same from the duo with Sakina?

The trio project in fact was a way to continue a work we started with music that approached composers like Michael Pisaro or things related to American minimal music. For a few years now, I’m really interested in a quiet way of making music. I got bored with a lot of amplified music. Amplifying acoustic instruments, for me, often changes the way I play and it’s not really a good feeling. On the other hand, Sakina’s solo record is very much based on the powerful saxophone sound and a sax is a loud instrument. You don’t play it the same when you play it really quiet. The duo we did recently in Portugal was much more powerful than what we do as a trio, and that will probably be the case for the concert in Antwerp as well.

Your most famous band is probably the quartet Kaze, with pianist Satoko Fujii and the trumpet players Natsuki Tamura and Christian Pruvost. Its sound is almost instantly recognizable, partly because of the instrumentation consisting of piano, drums and two trumpets, but also because of the consistancy of the compositions, which all seem to be part of a huge body of work. And that’s remarkable because the compositions are contributed by all of the members. How long has the quartet been active now? For about 15 years?

We started in 2010. I already knew Satoko and Natsuki for a while. The first time they came to Lille was in 2002 and that’s also when we first played together and discovered each other’s music. We kept in touch for years and when they came back in 2010, we organized a festival for which I proposed to do a quartet with two trumpets and no bass. If you remember, 2010 was the year that volcano in Iceland erupted ((Eyjafjallajökull, JC) and there were huge problems with flights around the world. Satoko and Natsuki only arrived here very late and we didn’t have time to work before the concert but we decided to do it anyway. It matched instantly. We also recorded our first album soon after that. It’s important to mention that Kaze is not anybody’s band, but a collective thing. Every member writes the music as you already said, but the compositions have always been frameworks for free improvisation. In fact, for a year now, we decided not to write music anymore and just improvise which is a big thing for us. Christian and me we were always pushing to do only free improvisation and to see what it does. It works quite well. It’s funny because for the last concert we did, the music turned out to be not so different from when we played the written stuff.

The most recent Kaze-album ‘Crustal Movement’ (2023), with Ikue Mori as a guest, is something special. Because of the pandemic, you didn’t have the opportunity to record it together, but you found some interesting ways to have a kind of live interaction. Could you tell me how the recording process came about?

In Japan the lockdown was quite strict and we also couldn’t always get out of the country. We had made plans for touring but everything got cancelled so we came up with the idea of making a kind of long distance album. Nothing that hasn’t been done before, expecially during that period, but I wasn’t really sure it was a good idea. We decided that each of us would propose some written stuff that we would all record. Satoko and Natsuki recorded in Japan and Ikue in New York while Christian and I recorded our parts in Lille. We also had the idea that it could be interesting to play live with the sound files of the others during a concert and to record the result. That way we could have an audience, because that is really important to us. Personnaly, I don’t play the same when there’s no people in front of me. So Christian and I played live with the recorded sound files of the others in front of a live audience and we recorded that. It worked well and some of these recordings ended up on the record.

The Kaze records are released on Circum Disc, the label connected to the Muzzix collective, which you have been running for years. You release both hard copy and digital albums. How does the future look for vinyl and cd’s from your point of view?

I’m still very attached to the physical stuff and to have an object in my hand. What I can see with this kind of music is that digital music is not as big as it is in other genres, although it is growing. And ofcourse, we make less physical copies for each release because we sell less. But still, without cd’s or vinyl we wouldn’t make any money. The physical sales allow us to reimburse a bit of production costs and it makes future projects possible. But what vinyl is concerned, I’m not so sure about the future. The cost is high and it has become a kind of luxury product. I’m not ready to sell records for 30 euro’s or more. We try to keep the price of our releases as low as possible and maybe that’s not a good strategy (laughs), but cd’s are definitely still alive!

Is Circum Disc available on streaming platforms like Spotify? I have spoken about this with quite a lot of musicians in recent years and some refuse to put their music on these platforms because they pay artists close to nothing. Others see it as a way to reach new audiences, something they wouldn’t be able to do in other ways.

Our music is on Spotify yes. My position has always been that the most important thing is to promote the music. We founded the label in the same way. It is also related to the collective. There isn’t really a professional environment for our music anymore with producers, recording companies etc. So everything is done in a DIY approach and with the realization we won’t make money with the recordings. I, for example, I don’t use Spotify. I don’t use any streaming service. But I know that’s it’s a way for a lot of people to discover what kind of music they’re into. For sure the system behind Spotify and others is really bad and not artist-friendly but we want people to access our music and that’s a way for sure. A bad way probably (laughs). I guess I’m just trying to say that people should buy cd’s if possible or albums on Bandcamp instead of these streaming services.

How people experience music has also changed drastically with social media, digital music, streaming etc.

That’s why going to concerts remains essential. The best way to get into this kind of music is to go and see concerts. It’s the easiest way to access it when you’re new to it or don’t know it well.

One of your recent albums is ‘Dead Dead Gang’ with a quartet consisting of Maryline Pruvost, Barbara Dang and Gordon Pym. The music is inspired by Alan Moore’s novel ‘Jerusalem’. I’m always interested to know what people are reading and/or listening to at the moment. Do you have anything you’d like to share?

Well, I went to a concert of The Necks yesterday. They played in Tourcoing, close to where I live. I’ve seen them quite a few times and even organized concerts with them years back. I really love that band, they’re a big influence on me and I love their concerts. Bu the concert experiences are really different from the albums. For a few years I’ve been really in love with Richard Dawson, the English guitar player and singer. He can bring in some experimental stuff in a really pop way of making music and I think that’s really interesting. Oh, yeah, there is a really beautiful album released a few weeks back by Anthony Pateras and Stephen O’Malley, with acoustic guitar and piano.

I’ll check that out for sure! And what about books or other things you might be reading?

I’ve been reading a lot and I can be a monomaniac in reading, meaning I discover one author and I want to read everything he or she has ever written. Alan Moore is one of those examples a few years back. Just now I’m reading stuff by the Spanish writer Manuel Vázquez Montalbán which I really love. It’s noir fiction, a series of crime novels centered around the detective Pepe Carvalho. I think most of the books were written in the seventies or eighties. Highly recommended!