HEAD to HEAD

Dave Rempis

‘Head to Head’ is a brand new series of interviews by Sound in Motion’s Joachim Ceulemans, talking in depth with artists appearing in the Oorstof concert series, the Visitations residencies, the Summer Bummer Festival or who have a release on the Dropa Disc label. These in depth interviews will be used to promote the upcoming events and releases and who knows maybe they will end up bundled and printed one day.

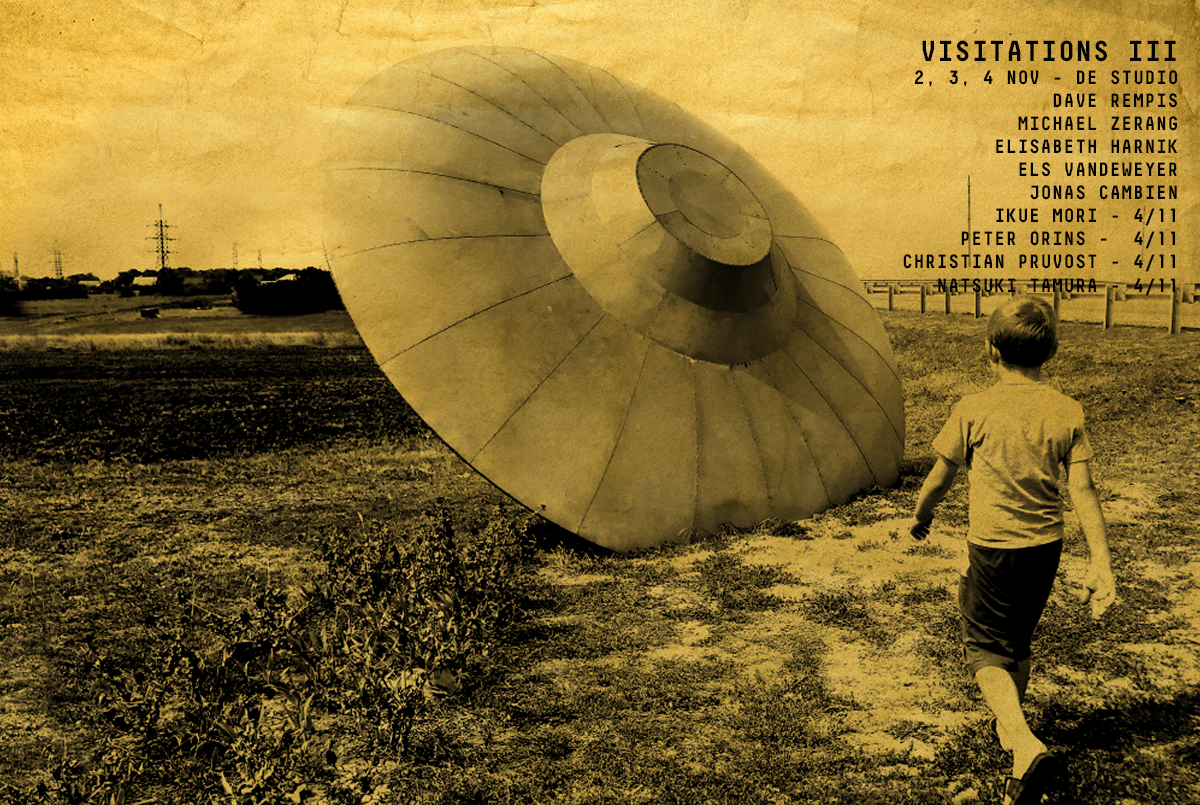

For the second interview in the series, Ceulemans talks to reed player Dave Rempis, one of the central guests of the third Visitations event of 2022, which will take place at De Studio on 2, 3 and 4 November. Rempis will be joined by Elisabeth Harnik, Michael Zerang, Els Vandeweyer and Jonas Cambien and on November 4th special guests Ikue Mori, Peter Orins, Christian Pruvost and Natsuki Tamura will join the company for 1 day. More info and tickets can be found here!

Saxophonist Dave Rempis (1975) from Chicago is no stranger to the loyal visitors of Sound in Motion. He has played more than one memorable concert for the organization over the years, including shows with Ballister and From Wolves To Whales. Recordings of these shows were later released on our house label Dropa Disc. There were also passages with Kuzu, The Rempis Percussion Quartet (in an exclusive collaboration with some young Belgian musicians) and an ensemble with Jaimie Branch, the first concert on Belgian soil for the regretted trumpeter that was later released on Rempis’ label Aerophonic under the title ‘Tripel/Double’.

Rempis is tried and tested in all aspects of musical life. He has been active in the international improvisation scene since the late 1990s, mainly as a musician but also as a programmer and curator of concert series and festivals. He runs his own label (Aerophonic) since ten years and worked for the large Pitchfork Festival as business manager. He is also currently involved in the Hyde Park Jazz Festival.

You’ve been a loyal partner for Sound in Motion since the very beginning. Actually the connection already started years before the organization was founded, when Koen Vandenhoudt was still working in Kunstencentrum BELGIE in Hasselt. Do you remember your first time there?

Yeah, I remember it very well. I think it was in 2002 (2003 according tot he archives, JC) with Vandermark 5 on a double bill with the Noah Howard Quartet. As a young musician it was such a powerful experience to see Noah Howard live for the first time and to be on the same bill as him. It was a very exciting moment for me.

Do you remember the musicians Noah Howard played with that night?

I don’t remember the bass player and drummer but Bobby Few was the piano player. It was kind of an incredible evening because Tim Daisy and I were having a drink with Bobby Few afterwards. We were sitting on a table that was elevated on a platform near the bar. Bobby was talking about how great it was that younger musicians like us were continuing the tradition. Right after he said that, he got up to get another drink but het didn’t realize the table was up on a platform. He took a step towards the bar but the floor was about 15 centimeters lower than he expected so he fell down and did a complete header on the floor. There was blood coming from his forehead an all that. The sound of it was so loud that everbody in the room – and it was a big room – stopped talking and looked over. For a moment we didn’t know if he was dead or hurt but he instantly bounced back up and said “I’m fine, don’t worry”. So Christel took him upstairs to help him clean up a bit. But everything was fine, thank god (laughs).

That’s pretty memorable for your first time in Hasselt indeed!

Yes, from then on I played there quite regularly, but this was the first time working with Koen en Christel, who would later start the organization Sound in Motion. I visited with Ballister as well and I might have also played there with Tim Daisy and Frank Rosaly, both in duo.

When Sound in Motion was born in 2010, the story continued. You’ve been a regular guest during all those years. How would you describe the organization, for instance, to a musician visiting for the first time?

To me it’s an organization that builds a community. It’s nog just organizing a concert or presenting something. Sound in Motion has worked so hard to bring interesting musicians from all over the world to Belgium and at the same time building a local scene and trying to connect those worlds. But it’s not just the musicians, the audience is another aspect they’re constantly working on. They are exploring many different ways to expand that community.

For the last 20 years I’ve been an organizer myself here in Chicago in a venue called Elastic Arts and for many years we’ve exchanged notes about our experiences, certain artists we want to work with, funding models and basically how to organize small community-run spaces in an art form that’s not popular at all. My respect and admiration for Sound in Motion is huge. Also, for a lot of work they do, they don’t get paid at all. It’s total dedication. For instance, giving musicians a place to sleep, cooking for eveyone. There’s so much love and dedication in all this. I can’t think of any presenter who I’ve worked with for so long who is so generous in every way. For instance, there’s nothing like the family meal before the concert, right? Musicians, volunteers, everyone is just coming together to eat this incredible home cooked meal. There’s nothing that can beat that. Not even the fancy restaurants you sometimes get to eat at when you play a big festival.

You mentioned Elastic Arts as part of your organizing activities, but you’re also involved in the Hyde Park Jazz Festival Chicago if I’m not mistaken?

Yes, I’ve been involved since 2013. In 2017 I took over as operations manager. I do all the advance work with the artists, like traveling arrangements, technical stuff, etc. I’m in contact with all the venues because the festival has 13 different stages around the Hyde Park neighborhood. Churches, museums, etc. I’m overseeing the logistical aspects of the festival.

That sounds like quite a job.

It’s perfectly manageable in advance, but once the festival has started, it gets pretty crazy (laughs).

Let’s talk about you for I while. How did you get into this kind of music? And how would you describe the music you play?

Personally I like the term improvised music because it’s a good description of what I do. Sometimes I perform compositions but my focus these last years has almost been strictly on improvising. It’s a reflection of what I find to be the most challenging aspects of music, not having any type of scheme to fall back on. It’s also about loving and trusting the musicians I’m working with to come up with the most interesting things possible. I can try to write stuff for certain people but they probably will come up with something better on their own so why not let them do that (laughs).

Improvising is a strategy. When it pays off you can have free improvised concerts that are extremely powerful in a way composed music does not always reach. You can also fall flat on your face with the same band the next night. So it’s a risk, but one I find very rewarding.

Do you have a background in jazz?

Yes, in some ways. As a kid I started playing saxophone and my older brother played the clarinet. A good friend of my father was a clarinet player in Greek bands. My father’s Greek and I grew up outside of Boston, where there is a huge Greek community. We would hear that friend of my father play around the house and at dances, weddings and things like that which was very exciting for me. Growing up around that music helped set my interests in a different way than children who only heard the pop music of the early eighties. That’s how I got interested in saxophones and woodwinds. From then on I discoverd that the people who do the most interesting things on saxophones are always jazz musicians. My grandfather on my mother’s side was a big jazz fan and early on when I started playing he gave me a cassette with on one side a record by Coleman Hawkins and one by Charlie Parker on the other. I must have been about ten or eleven years old so I probably didn’t listen to it for a few years. But when I eventually checked it out, I really connected to Charlie Parker first and later on with Coleman Hawkins. I started to understand what was going on in the music. I still have that cassette with my grandfathers handwriting lying here somewhere.

That was still in Boston. Later on you moved to Chicago where you studied ethnomusicology.

When I was 18, my plan was to do a double degree program in Chicago: music and something with local arts. After three months I dropped out of music school because I hated studying classical saxophone and it wasn’t the right place for me. But I was able to take a class with an ethnomusicologist called Paul Berliner, who did a lot of work on the mbira traditions in Zimbabwe. He went on to write a huge book on jazz improvisation that came out around 1997. He was also a trumpet player and did some work with Barry Harris and other people. That sparked my interest completely. At that point I didn’t even know that something like ethnomusicology existed. With my own family background and with my interest in John Coltrane, Yusef Lateef, Eric Dolphy and other musicians who brought in those non-western influences, I realized ethnomusicology was what I wanted to do. So I ditched my music degree and did an anthropoly degree, with a focus on music.

So in Chicago, how did you come into contact with free improvised music?

Once in Chicago I immediately started going to jazz clubs. There was a saxophone player at that time, Ed Petersen, who had an incredible band that played at the Green Mill every Friday night, which is still one of my favorite jazz clubs by the way. The band was a Willy Pickens on piano, Bryan Sandstrom on bass and Robert Shy on drums. That band just blew my mind and I went to the Green Mill almost every week that first year in Chicago just to see that quartet.

Then in my second year in Chicago I discovered a club called the Lunar Cabaret, where Ken Vandermark was booking a Thursday night series of music. I saw Ken perform there two weeks in a row, the first week with his band Steam that played the music of Albert Ayler, Ornette Coleman and Eric Dolphy. The next week with a band of Mars Williams called Witches And Devils, playing the music of Ayler. Those two weeks back to back absolutely blew my mind. I didn’t realize people still played that way. All I knew was what I learned in music school and what I read in Downbeat magazine: the young lions, guys in suits playing jazz in wine bars and stuff like that. I didn’t understand what had happened to the tradition of all that adventurous music that came from the sixties. It wasn’t represented anywhere, or at least not represented where I had access to it.

Together with the Lunar Cabaret, I started going to the Hot House, where a lot of AACM musicians were working. I saw Fred Anderson there for the first time and also Jodie Christian and Harrison Bankhead among others. I was so thrilled to see that people were still working with the kind of music that excited me as a teenager.

In one’s career, there are often some obvious deciding moments, like the experiences you just described. But there are also pivotal figures. When I think of Chicago, as an outsider, I would guess Fred Anderson is one of those people. You released a digital album with the band Triage on your label Aerophonic, that was recorded in 2005 at Anderson’s legendary Velvet Lounge. In the liner notes you give him some huge credits. Besides Fred Anderson, who would you pick as being of importance to you or other improvisers in Chicago?

Man that’s a heavy question! There are so many people. Everyone who contributes to the community is of importance. Fred was very important in building that community and having a place, an open platform where he invited so many different people to be a part of it. It has set a tone that many people have appreciated and absorbed in a way that they continued that legacy. The contributions can be big or small: from lending an instrument, curating a weekly or a monthly series of concerts or musicians going to each others concerts. All these things are gestures that help support the infrastructure that has been built. Mike Reed is a great example: he’s a drummer, a club owner, a presenter and he has built some pretty noticeable things. But there are so many people contributing in big or small ways. That said, I really want to mention Von Freeman, who passed away ten years ago. At the time I was coming up as a musician, Fred and Von were the two patriarchs of this scene. Fred was thought of as the “outside” player and Von the standard jazz player, which I find totally inaccurate by the way. Von hosted jam sessions at the New Appartement Lounge and that had a huge effect on generations of jazz musicians. He was also an amazing person.

During the Visitations residency, you’ll present a trio with Michael Zerang and Elisabeth Harnik. The first time you played together as a trio was ten years ago, but haven’t performed often since then right?

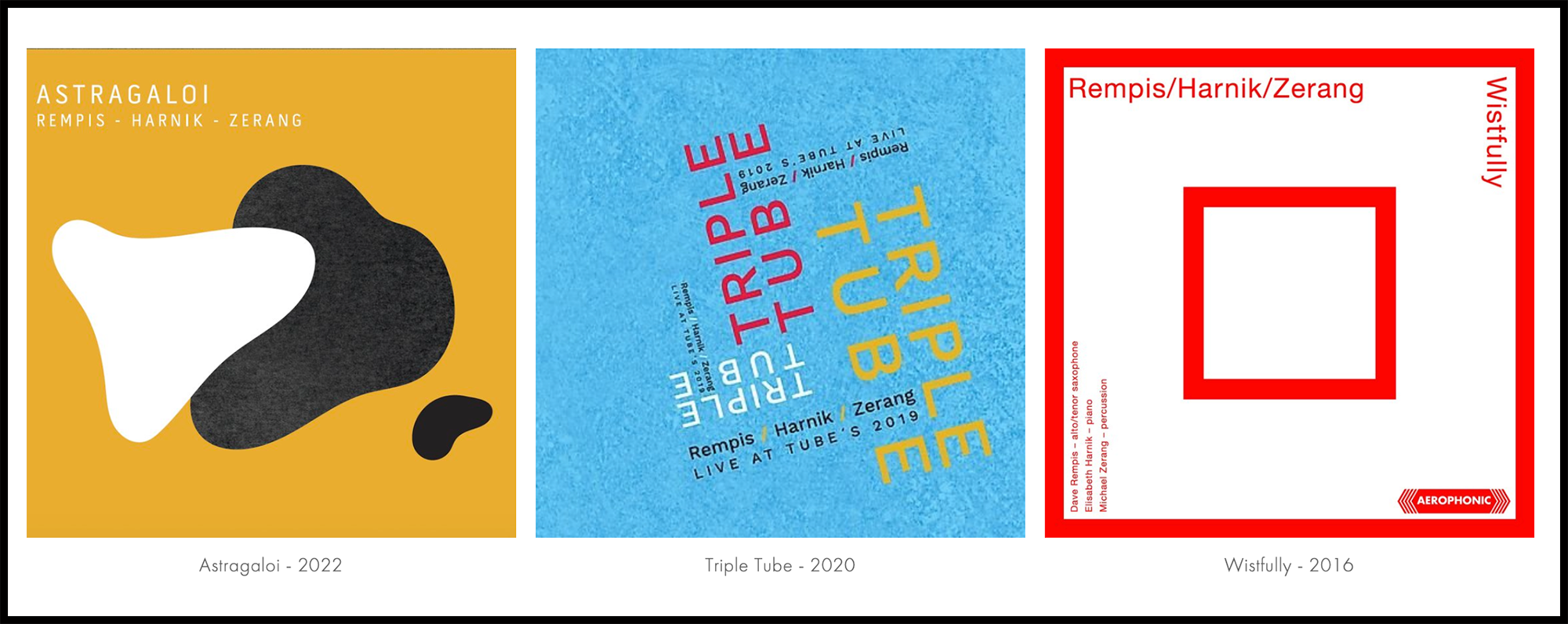

Our total number of gigs is probably five or six. Until now it could only happen when we were all in Europe and found the time to meet. The first concert we played in Graz and it was recorded for the national radio. We later released it digitally on Aerophonic. In 2020, right before the pandemic, we played in Austria and recorded the concert. That also came out on Aerophonic, on cd this time called ‘Astragoloi’

I was wondering about that. Did you realize what was going on at that time?

Yes. Everybody was feeling very uncertain. It was the last concert I had after a two week tour in Europe. A few days later I was on another tour in the US, in Saint-Louis. I remember being in the tour van, listening to the radio when the announcement was made that everything was about to close down. We ended that tour on March 14th, just days before the US went in complete lockdown. But even in Austria we knew there was something serious going on.

Did you feel it in the room when you played? I’m curious because those first weeks of the pandemic were really strange and filled with uncertainty. When you went to the store people almost screamed when you came too close to them.

There was a certain anxious energy. But at the same time, nobody had ever lived through a pandemic so nobody knew what to expect. It was right before the period where all those huge decisions were made.

‘Astragaloi’ was recorded at a tipping point in recent history.

For sure. But with Kuzu we recorded a record even closer to the actual start of the pandemic. Just days before everything was shut down, on March 13th. One of the last concerts before that very long break!

Did COVID change your approach to touring and playing?

COVID remains a concern. This past year I saw a lot of colleagues cancel tours because of it. Just last week Jeff Parker and Tortoise were in the middle of a tour in Chicago, but they had to cancel because a few people in the band had caught COVID. It’s still hanging over our heads. It can wipe out the finances when you have to cancel a few shows.

Most people I know are ready and willing to play and go on tour again. But the willingness might have changed in some ways. For me personally, I’m not super excited to go on tour anymore where I don’t make any money and have to sleep on the floor. That era, for me, is over. My threshold has changed a little bit (laughs).

Enough with the COVID. In Antwerp you will be joined by two Belgian musicians: Els Vandeweyer and Jonas Cambien. Are you familiar with them?

I’ve known Els for more than 10 years. We’ve played together in Hasselt, when we shared the bill there with Vandermark 5 and a band of Els that featured Tim Daisy, Kent Kessler and Fred Lonberg-Holm. She came to Chicago a couple of times, where we got to know each other.

Jonas I don’t know very well but we’ve been in contact a lot the last few months. I also saw his trio in Chicago around 2019.

The last day of the residency, some other musicians drop by as well. The one and only Ikue Mori, Peter Orrins, Christian Pruvost and Natsuki Tamura.

I’m really excited for that. You may know the band Kaze with Satoko Fujii, who unfortunately couldn’t make it. We’ve had them here at Elastic Arts a few times and it’s such an fantastic group. I really love what they do. I don’t know if you’ve heard but it was just announced that Ikue Mori received a MacArthur Genius Grant, together with Tomeka Reid. She’s really legendary.

Did you all talk about how you’ll tackle the residency?

We talked aobout some of the groupings. The first night we’ll probably have some chance groupings. I’ve done this before. Usually when I do this each musician gets assigned a number on a paper and we just pull the numbers from a hat. In improvised music it’s a great way of doing it. The result might be the same or even better than when you discuss or debate about what you want to do. And it’s more challenging because you might end up with two saxophones and a bassoon or three piano’s.

The second night we’ll present the trio with Elisabeth Harnik and Michael Zerang. There will be another set with Els and Jonas. And then the third night, if I’m not mistaken, the newly arrived musicians will open first and afterwards we’ll all play together.

What do you consider crucial aspects of a residency?

There’s different kinds of residencies. You can sit alone in a cabin in the woods for a week, but in a context like this, what’s crucial is the time you have both on and off stage to get to know the musicians. You don’t have to travel like when you’re on tour. You can actually relax and play in several different contexts with musicians. That’s how you get to know people, see how they handle different groupings and instrumentation. It’s nice to not feel rushed. You know you get several opportunities to play together and that helps to really develop something.

Your label Aerophonic is almost ten years old now. The first releases were all physical, mostly cd’s. After a while, you started with digital releases as well. Why?

For one thing, you can turn it around a lot quicker. You can put out a recording that was recorded a few weeks earlier. Also, a lot of people listen digitally. There are still people buying cd’s and vinyl, but even then they listen to the music online. From a financial perspective, the biggest part of the cost is the manufacturing of the phycial item. It’s also very time consuming to ship everything out. Online, everything is low maintenence. You see, there’s a lot of reasons to do digital releases.

You have an outspoken opinion on streaming platforms and the business models they use.

For the music we’re making, it just makes no sense at all. For an artist at the top level of pop music, I can understand why they’re willing to give up revenues for records because they can use it to book concerts. That’s their main revenue stream compared to 20 years ago. Ticket prices have gone up a thousand times and it’s all about VIP experiences, special packages that can cost 500 or even 2000 dollars and stuff like that. For a small artist like myself, selling 500 copies of a record when I can keep expenses low, it really means something. I can generate an amount of revenue off that to support my career and my life. If 50.000 people listen to my record on Spotify – I don’t put my music on Spotify by the way – I would still make more money when I sell one actual physical cd. When people book one of my bands, it’s not because they checked out the amount of streams I have on Spotify or the amount of views on TikTok, they’re interested in the art that’s being made and they want to sell tickets for the concert.

Is Catalytic Sound an answer to that?

It’s an interesting experiment. Right now there are 30 artist involved, quite a lot of people so just managing that is complicated. You have to figure out how everybody can give input that is helpfull and productive. We’re working on the Catalytic Sound Festival right now actually, that will take place on eight different locations in the world: Chicago, New York, Washington, Trondheim, Amsterdam and other places. It’s expanding in an interesting way. Hopefully it can be a good example of how artists can work together in an alternative way.

You’ve been touring for about 25 years now. What evolutions do you see in the international scene?

The US hasn’t changed a lot. There is some funding, but we still depend on DIY networks of local presenters who are interested in this music. There are more grants available for this music than before, but still nothing compared to Europe. On the European scene a lot of the funding has dried up a bit. The touring model is looking more and more like the model here in the US, where the presenter can maybe pay a fee of some sort when in other cases you play for the door money, but the presenter can provide you with a place to stay.

Record sales have changed a lot. In the late nineties and early twenties you could sell 50 records at a show. Now, if you sell 15, it’s a good night. People tend to find the music online somewhere. Music is uploaded on YouTube for free, for instance.

The audience depends on where you play. The hardcore following in Europe, that came up from the end of the sixties, is still a huge part of the fanbase. They’re also still buying a lot of records. In Antwerp, but also in Vienna or Berlin, you often see younger people in the audience. There’s interaction between local musicians and touring musicians. They say the audience is a reflection of the scene and vice versa. If young people are playing on stage, you have a lot more chance to see younger people in the audience.

Dave Rempis interviewed for ‘Head to Head’ by Sound in Motion’s Joachim Ceulemans

© Sound in Motion vzw – 2022